Blog

No alto da Amazônia,

surge uma nova espécie de sapo

Expedição liderada por cientistas da USP descobriu o anfíbio na Serra do Imeri, uma cadeia isolada de montanhas no norte do Amazonas

Neblinaphryne imeri: uma nova espécie de sapo descoberta na Serra do Imeri, no norte da Amazônia -- Foto: Antoine Fouquet

A new species of frog appears in the upper Amazon

An expedition led by USP scientists discovered the amphibian in Serra do Imeri, an isolated mountain range in the north of Amazonas

Neblinaphryne imeri: a new species of frog discovered in Serra do Imeri, in the northern Amazon -- Photo: Antoine Fouquet

High up on a mountain in the northern Amazon, the song of a little frog attracted the attention of researchers. It was a song they had never heard before; in a place no one had ever surveyed before – two strong indications that this was a new species.

High up on a mountain in the northern Amazon, the song of a little frog attracted the attention of researchers. It was a song they had never heard before; in a place no one had ever surveyed before – two strong indications that this was a new species.

Hearing the animal was easy, finding it in the middle of the vegetation, not so much. It took scientists four days to capture the first specimen, and two years to scientifically determine its identity. As expected, it was a new species, which they named Neblinaphryne imeri, after the mountain range in which it was discovered: the remote Serra do Imeri, on the border between Amazonas and Venezuela.

The paper officially describing the species was published on September 25th, in the scientific journal Zootaxa, signed by a group of researchers from the Institute of Biosciences (IB) of USP, the Center for Research on Biodiversity and the Environment (CRBE) from France, and Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, in Spain, who took part in a pioneering expedition to Serra do Imeri in November 2022.

The researchers spent 12 days camping on the top of a mountain next to Pico do Imeri, at an altitude of almost 1,900 meters, collecting the greatest possible diversity of plants and animals around the camp, in one of the most preserved and least known regions of the Amazon. They returned home with more than 260 species of flora and fauna with them, several of which are considered new to science. Neblinaphryne imeri is the first of these to have its description published in a scientific journal – which is equivalent to a birth certificate for the species.

One of the frogs collected on the expedition and used to describe the new species, named Neblinaphryne imeri - Photo: Leandro Moraes

Landscape of Serra do Imeri, with the expedition camp and Pico do Imeri in the background – Photo: Herton Escobar / USP Imagens

“As soon as we arrived, we heard the call of a little frog that was clearly new, at least to us. And, from the very beginning, we tried to find who was making that sound, but it was difficult because this species is very small and sings well hidden in the moss,” says biologist Antoine Fouquet, a CRBE researcher and long-time collaborator with the IB team, where he did his post-doctorate in 2010-2011. It was he, along with IB colleague Leandro Moraes, who collected the first specimen of the new species in Imeri.

To find the animal amid a tangle of moss and roots, it was necessary to use the playback technique, in which the researcher records the animal’s call and plays it back to it, hoping to lure it closer or make it move, revealing its location. “I was looking for the singer, started digging with Leandro, and after a few minutes of playback, an animal jumped out when we were about to give up,” said Fouquet, in an interview with Jornal da USP.

Click to hear the call of the Neblinaphryne imeri – Credit: Taran Grant

Over the next few days, the team caught other nine specimens of the species (seven males and three females in total), each between 1.5 and 2 centimeters long. Neblinaphryne imeri is predominantly brown, with white dots and a few yellow spots all over its body – mainly on the ventral side. The females are slightly larger than the males, who sing predominantly at dawn and dusk. Some specimens were found in forest areas, buried in moss, while others were in open areas, hidden in vegetation or among bromeliad leaves.

The specimen that served as a model for the description of the species (known as the holotype) was a 1.6-centimeter male, collected on November 16th, 2022, at an altitude of 1,800 meters – detected while singing at the entrance to a tarantula burrow. (The animal chosen as the holotype is not necessarily the first to be collected, but the one with the best set of information associated with it, such as recordings of the call, photographs in the wild, the exact location of the collection point, and tissue samples).

All the animals collected on the expedition are in the biological collections of the Zoology Museum of USP.

Unexpected relationship

From the beginning, the researchers realized that this was a new species, but they didn’t know which lineage it belonged to – in other words, which branch of the amphibian family tree it fit into. The preliminary hypothesis, based on a visual assessment of the animals in the field, was that it was a new species of Adelophryne, a genus of frogs that occur both in the lowlands and high up in the mountainous formations of the northern Amazon, known as tepuis. More detailed molecular (DNA) and morphological analyses, however, pointed in another direction.

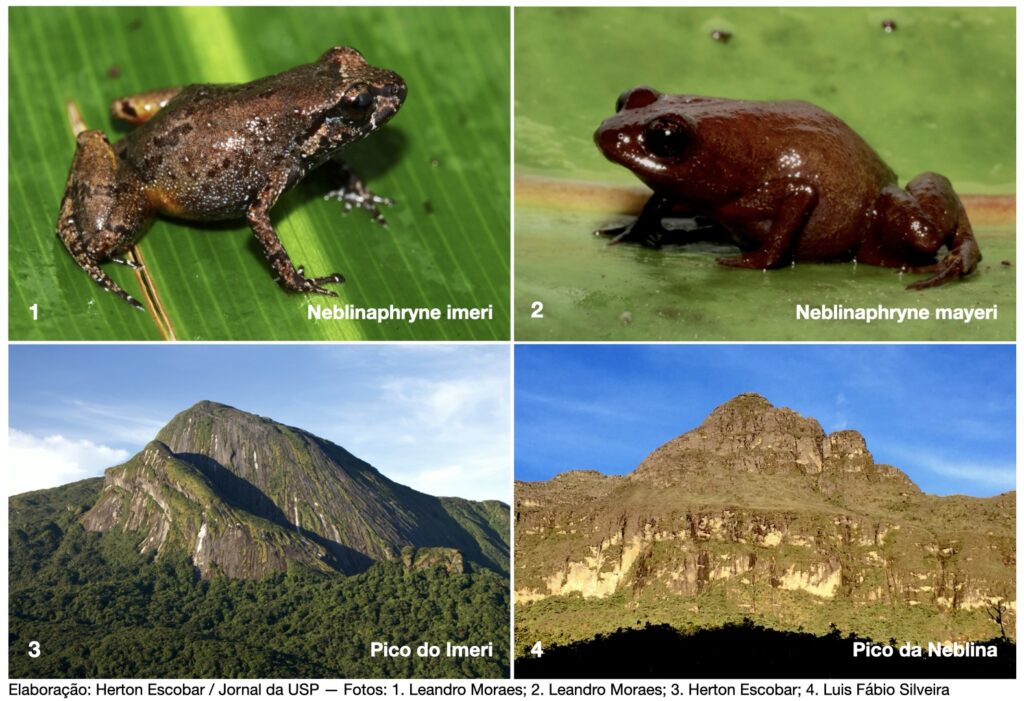

To the researchers’ surprise, the data indicated that the closest relative of the new frogs was Neblinaphryne mayeri, another species that the same group of scientists had discovered in 2017 on an expedition to Pico da Neblina – Brazil’s highest mountain, which is 80 kilometers west of Pico do Imeri. That’s why the new species was named Neblinaphryne imeri. (In the case of Neblinaphryne mayeri, the name of the species is a tribute to General Sinclair Mayer, of the Brazilian Army, who was instrumental in carrying out the expeditions).

Sister species: Neblinaphryne imeri and Neblinaphryne mayeri are lineages that diverged from a common ancestor, occupying distinct mountain groups in the northern Amazon.

“The most incredible thing is that the two species are very different morphologically. We never imagined that they would be sisters,” says herpetologist Miguel Trefaut Rodrigues, professor emeritus at IB and mentor of the two expeditions – to Pico da Neblina and Serra do Imeri. “You can see that external morphology is also often misleading.”

It was only by analyzing the genetic and osteological characteristics, obtained through a CT scan of the skeleton, that the researchers were able to see the internal similarities beneath the external differences, which revealed the unexpected relationship.

Today, the highest parts of the Neblina and Imeri massifs are separated by 20 kilometers of lowlands, which act as a barrier to the dispersal of these animals between one group of mountains and the other. In other words: the species are completely isolated from each other, even though the geographical distance between them isn’t that great – especially by Amazonian standards.

A world apart

All of these high-altitude ecosystems in the northern Amazon are known as Pantepui. Its trademark is the imposing flat-topped mountains and bare walls, such as Monte Roraima and the Pico da Neblina massif itself, which inspired the story of Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World.

From an evolutionary point of view, it’s as if the Pantepui were a separate biome from the Amazon, hovering over the lowlands of the forest. The environmental conditions at the top of these mountains are different from those below them, mainly due to the temperature; and the species that have adapted to living at altitude are unlikely to come down to the lower, warmer areas of the biome. In this sense, it’s as if these mountains were archipelagos in an ocean of forest, which is insurmountable for most of the plants and animals that live on their “islands”.

Map showing the location of Pico da Neblina and Serra do Imeri, where expeditions led by USP researchers have discovered several new species

The Pico do Imeri and Pico da Neblina massifs are located in the northern Amazonas, within two protected areas: the Yanomami Indigenous Land and the Pico da Neblina National Park.

Scientists therefore suspect that the two species of Neblinaphryne are endemic (exclusive) to their respective massifs. Genetic evidence suggests that they originated from a common ancestor who lived in that region 55 million years ago, when the Neblina and Imeri mountains were probably connected. As the landscape changed and the massifs became isolated from each other by erosion (due to climatic and geological processes), each population of frogs also became more distant and different from each other to the point where they became distinct species. “We are still at a very early stage of trying to reconstruct this history, which, for being very old, is very complex,” says Rodrigues.

As far as the researchers could tell, the Pico da Neblina species lives in areas of open vegetation above 2,000 meters above sea level and shelters mainly under rocks, while the Serra do Imeri species lives between 1,700 and 2,000 meters above sea level, occupying both forest and open vegetation areas. The need to adapt to these different environmental conditions, according to the scientists, could explain why the species have diverged so much in their external morphology. Their calls are also completely different.

“These high regions have an island configuration and typically each island has endemic species because of its isolation,” explains Fouquet. According to him, Pantepui is home to at least 11 genera of endemic or subendemic amphibians, which do not descend – or very rarely descend – below 1,000 meters of altitude. “These genera evolved in isolation over tens of millions of years, so Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wasn’t so out of touch with reality when he wrote The Lost World, imagining dinosaurs and pterodactyls on top of tepuis.”

Pieces of the puzzle

Scientists still have other four new species of amphibians and three lizards from Imeri to describe, at least. “This is the first of several articles and the first of several species,” says Professor Taran Grant, an amphibian specialist at IB-USP, who also took part in the expedition to the Serra do Imeri and signed the paper in Zootaxa.

Discovering, describing and studying the life history of new species is one of the most basic and important tasks for understanding and conserving biodiversity. “The first question everyone asks us is: How many species have you discovered in Serra do Imeri? So that’s the first question we have to answer,” says Grant. “Good or bad, all conservation efforts and initiatives are based on species diversity.”

Both Serra do Imeri and Pico da Neblina are already within protected areas – the Yanomami Indigenous Land and the Pico da Neblina National Park – which are not under direct pressure from deforestation in that region, at least for the time being. But climate change, driven by global warming, threatens the biodiversity of the entire biome, and is especially problematic for these high-altitude species, which are adapted to milder temperatures and have nowhere to run in the event of warming.

Researching and protecting these species is therefore crucial both to understanding the past and to safeguarding the future of Amazonian biodiversity. “We are getting to know a part of the planet that was completely unknown, from the point of view of science, and this ends up filling in extremely important gaps in the history of life on the planet, in South America and the Amazon, as if they were pieces of a puzzle,” explains Rodrigues. “Look; we’ve discovered a lineage that we didn’t even know existed, 55 million years old, and this could tell us a story about our continent that is much older than we imagined.”

Describing the species is only the first step in this process. Scientists still plan to carry out further genetic research and comparative studies to better understand the relationships and evolutionary history of these lineages.

Jornal da USP accompanied the researchers in Serra do Imeri in 2022 and produced text and video reports about the expedition, which can be watched here and here. The project was carried out with the support of the Brazilian Army and the Biota program of São Paulo Research Foundation (Fapesp). Researchers Renato Recoder, Agustín Camacho, José Mário Ghellere, and Alexandre Barutel also signed the paper in Zootaxa.

More information with the professor Miguel Trefaut Rodrigues (mturodri@usp.br) or Antoine Fouquet (fouquet.antoine@gmail.com)

*Intern under the supervision of Moisés Dorado

A reprodução de matérias e fotografias é livre mediante a citação do Jornal da USP e do autor. No caso dos arquivos de áudio, deverão constar dos créditos a Rádio USP e, em sendo explicitados, os autores. Para uso de arquivos de vídeo, esses créditos deverão mencionar a TV USP e, caso estejam explicitados, os autores. Fotos devem ser creditadas como USP Imagens e o nome do fotógrafo.